Difference between revisions of "John Wesley Gladstone Turner"

From Our Contribution

(→External Links) |

|||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

| enlistmentdate = 17 Aug 1914 | | enlistmentdate = 17 Aug 1914 | ||

| rank = Private | | rank = Private | ||

| − | | unit = 11th Battalion, A Company | + | | unit = 11th Battalion, A Company |

| embarkationdatefrom = 2 Nov 1914 | | embarkationdatefrom = 2 Nov 1914 | ||

| embarkationdateto = 3 Dec 1914 | | embarkationdateto = 3 Dec 1914 | ||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

| monument2 = [[Armadale and Districts Roll of Honour]] | | monument2 = [[Armadale and Districts Roll of Honour]] | ||

| monumentnote2 = | | monumentnote2 = | ||

| − | | monument3 = | + | | monument3 = [[WA State War Memorial]] |

| monumentnote3 = | | monumentnote3 = | ||

| monument4 = | | monument4 = | ||

Latest revision as of 13:09, 11 December 2023

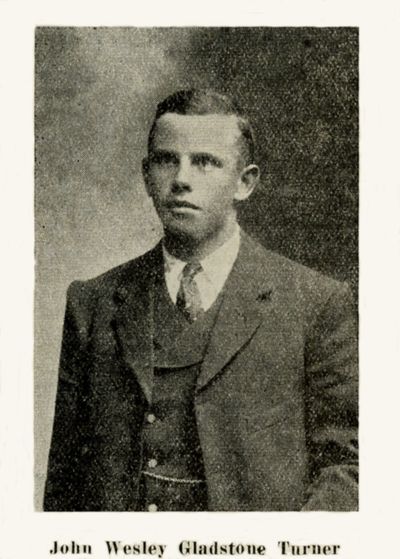

The Drill of the Foot-Hills 1916 Aug-Sep edition p.21 | |

Headstone from Shell Green Cemetery, Anzac Cove | |

| Personal Information | |

|---|---|

| Date of Birth | 24 Jan 1883 |

| Place of Birth | Sutton Scotney near Winchester, England |

| Death | 6 Aug 1915 |

| Place of Death | Leane's Trench, Gallipoli, Turkey |

| Age at Enlistment | 31 years, 7 months |

| Description |

5'7½" (1.71m) tall ; 155 lbs 70.307 kg ; fair complexion ; brown eyes ; brown hair |

| Occupation | Sleeper hewer |

| Religion | Church of England |

| Address | 'Cranbourne', Beenup, Western Australia |

| Next of Kin | Mother , Mrs Sarah Turner |

| Military Information | |

| Reg Number | 108 |

| Date of Enlistment | 17 Aug 1914 |

| Rank | Private |

| Unit/Formation | 11th Battalion, A Company |

| Date of Embarkation | 2 Nov 1914 ‒ 3 Dec 1914 |

| Ship Embarked On | HMAT A7 Medic |

| Fate | Killed in Action 6 Aug 1915 |

| Monument |

Armadale War Memorial (Beenup panel) Armadale and Districts Roll of Honour WA State War Memorial Australian War Memorial |

| Medals |

1914-15 Star British War Medal Victory Medal |

War Service

One of the very first to enlist in Western Australia, he was allocated on day one to A Company of the 11th Battalion.

While the AIF Project website indicates that Turner embarked on the Ascanius (which also carried troops from South Australia's 10th Battalion), the Battalion history book indicates that 'A' and 'B' Companies of the 11th Battalion embarked on HMAT A7 Medic which they shared with men from the 12th Battalion (Joint Tasmanian and Western Australian unit) on October 31st. After training in the desert near Cairo, Turner and the rest of the Battalion sailed on 2 Mar 1915 aboard HMAT A23 Suffolk to Mudros harbour on Lemnos Island, where they were to remain for seven weeks. Turner as a member of 'A' Company was transported from Mudros harbour to Anzac Cove on the British battleship HMS London.

Along with 'C 'Company they formed the first line of the covering party from the 11th Battalion, and thus were amongst the very first ashore to be met by machine gun and rifle fire. With unloaded rifles, but with bayonets fixed they charged inland up very steep hills. 'A' Company was involved in heavy fighting until the battalion was withdrawn from the front late on Apr 28 1915. They had suffered 34 KIA, 190 WIA and another 154 men were missing. By May 5th when the battalion went into reserve, the numbers were 38 KIA; 200 WIA ;197 Missing, total losses of 435 men. Turner was one of 40 men of the 11th Battalion who lost their lives in a subsequent fierce battle adjacent to Leane's Trench near Lone Pine.

In a letter home to his mother in June, Jack tells of Turks lining up preparatory to charge, but not doing so despite making an "awful Noise". He didn't sleep that night, as he hadn't slept for the first 4 days ashore. He had been detailed to 'Observer duty' one night when he narrowly escaped becoming a victim of a Turkish sniper. His hat had been shot off his head, but he escaped with a slight graze on top of is head.

Game To The Last p.xviii

"John Turner of Metcalf's A Company, wrote to his father that it was 'sickening to see how many of our fellows had been hit. So many of our pals were missing when the roll was called, Dad, and I think it was not until then that I realised how awful war was....Old South African soldiers tell me that they never saw such a terrible time in the Boer War' "

At page 29, Turner describes troops attending sick parade with a

"well-simulated husky voice, a pathetic woebegone look....On coming out, the patient nods if he has been lucky, and races for a good breakfast."

On the 24th of May 1915 an armistice was called to allow the dead of both sides to be buried to improve health of all concerned. At page 90, Jack Turner observed from the safety of a trench.

"We killed more than I thought the morning of their attack. Can only see a little of what is going on. The order is to keep out of sight."

At pp 90 - 91 Turner's notes of 8 June show that he was

"In supports during the morning, but told off for tunnelling operations in connection with a new firing line in front of A Company. Went on shift at 12 mid-day" He later noted "No 3 platoon of A Company with a platoon of each company of our battalion were sent to capture a trench 250 yards to our front under Major X. X was drunk. R never left the saps and M lost his way and his nerve, consequently the result was a fiasco. Which was a disgrace to the battalion." They came back about 3.00 am having got bushed and scared and having made no attack at all."

When off duty, Jack Turner...

"Went round to Shrapnel Gulley...Snipers still bad. Fred Fancote is around here...Turks...evidently understand the art of trench digging. Each trench if captured, can be enfiladed from each flank. Those we took had to be left again at daybreak. They are also good at creeping up individually and sniping close to our trenches. Early in the game single snipers were caught inside our line...They also hide their machine guns very well..." "We are handicapped for want of scope for our artillery for we cannot manoeuvre them at all. These field guns are run out and a few shots fired as quickly as possible and then run back into the pit before the enemy can reply or they would be blown to pieces. The 8th Field Artillery have been especially complimented by the Brigadier General. They are from W.A."

page 125 of "Game to the Last" records

"On Wednesday, 28 July, Jack Turner moved into supports...Much bomb throwing last night'. Pat Foley was in the act of throwing one of the 'home made' bombs when it exploded, blowing of his hand and 'otherwise badly wounded him'.

Jack Turner noted after fierce fighting at Leane's Trench the arrival of 90 reinforcements for A Company (normal full strength was about 240), so very heavy casualties had been inflicted on them. Jack, survivor of the Landing and Gabe Tepe raid, was eventually killed defending Leane's Trench against a fierce Turkish 'bombing' counter attack. (p.153)

Jack's death was included in the 76th Casualty List, published Friday 17 Sep 1915 in the Western Mail. "Jack Turner is the son of Mr S. Turner, of Beenup, who has been associated with our churches ever since they were planted. Mr Turner often occupies our pulpit, and both Kelmscott and Armadale congregations sent a message of sympathy to the bereaved family."[1]

A cable sent by Jack on 3 May 1915 never reached his family and his father wrote in July 1915 seeking an explanation.

Jack Turner from Beenup (Extract from The Drill of the Foothills August - September 1916 edition)

James Winning of Bedfordale and Jack Turner of Beenup, were among the first to join the expeditionary force. Both took part in the Gallipoli campaign. They were killed on the same day, 6th August, 1915. News of their deaths reached us on the same day and they are buried in the same grave. It is therefore fitting that our record should start with them. Mr Winning has not yet supplied us with particulars of his son, but the correspondence and diary of Jack Turner has been placed at our disposal and our information is drawn from that source. He was a close and painstaking observer, wonderfully descriptive and his narrative is interesting from start to finish. Had his bent been in that direction he would have been a superior writer. In producing his compilations we are rather puzzled what to leave out and we will let him tell his own story as much as possible.

In his communications with his friends he was extraordinarily careful; in the letters we have read there was not a line blotted out by the censor. The tone of his writing is breezy and optimistic. There is no trace of moodiness or dread, Each day's events are set forth in a terse matter of fact manner. He may mention that a large number of his comrades are hit or that he has to be careful with his cigarettes; he may be stating the fact that there are eight acres of Turkish dead in front of his trench and that the stench is awful or that the view across the bay is exquisite in its loveliness; it is all evenly written down, briefly and concisely, and the picture produced on the imagination of the reader is clear and full. And yet there is an undercurrent of a sadder texture, the yearning to know the everyday doings at home, speculation about the price of the apricots and every now and then the desire to have a yarn with dad.

The Turner family came originally from Dorset shire, resided for some time in Hampshire, and came in 1895 to Australia. They settle on the land in Beenup and the home has been there since. Jack was between 12 and 13 years of age when he came to the district and may be said to have been brought up in it. He was the youngest son of Mr. Samuel Turner. He placed himself for a couple of years at Scotch College and frequently took part in competitive essays. On one occasion his tutor remarked that his essay was as good as some of the leading articles in the "West Australian." He joined the volunteers within a week of the outbreak of the war, went through his preliminary training at Blackboy Hill and left with the 11th Battalion in the latter end of November, 1914.

The troopship SS Medic in which he sailed, formed a part of the largest fleet that has ever been seen on the Indian Ocean, whether the number of ships, their tonnage or their variety is taken into consideration.

The precise number and composition of the fleet was not made known at the time, for the German cruiser Emden was then doing all the damage she could: there were roving squadrons of the German fleet still abroad upon the high seas and secrecy was a necessity. It was during the passage of this fleet that the Emden was battered to pieces on Cocos Island. Australia did a bit of flag flapping over that event. Jack alludes to it thusly:-

"Of course you know that the Emden was captured by the Sydney, but there was a good deal made out of a very ordinary capture, as the Emden must have been outmatched both in speed and in the power of her guns. Anyhow the fight lasted some few hours and the Sydney is a boomed thing now. The Emden did not surrender until every gun had been put out of action, and over a hundred and forty killed and wounded. She was on fire right amidships and on shore. The victory was the first wireless message the fleet received after leaving Fremantle".

The fleet called at Colombo, but the troops were not allowed ashore, neither were they permitted to trade with the native craft that came to sell them things. They knew little or nothing of the progress of the war, only the barest outlines of the chief events and not until they were in the Red Sea were they made acquainted with the fact that their destination was Egypt. Only one accident marked the journey. Two troopships bumped into one another and a man was drowned. Among such a mass of men, living for the most part under entirely new conditions, there is bound to be some sickness, but most of it became pronounced shortly after the arrival at Mena Camp.

"We have lost some 160 since the troopships left Australia and New Zealand and the hospitals are full of sick. The most prevalent form is pneumonia and pleurisy which seems to attack the strong with greater violence than the weak. Then of course there are also other diseases which one can blame to the 38,000 licensed prostitutes which invest Cairo."

EGYPT It was a masterstroke of German diplomacy to persuade Turkey to go to war with them against the Allies. It was thought to give Germany the advantage of cooperation of the whole Mohammedan world and stretch a broad belt of fanatical enemies right across the centre of the British Empire. For from the Atlantic to the Himalayas the nations are Mohammedan; fierce and warlike, civilisation has more than once stood in danger of being over-run by those nations and the Sultan of Turkey is their nominal spiritual head. Moreover the most considerable of those nations had grievances against their European rulers. Algeria and Tunis are French, Tripoli is Italian, Egypt had only of recent years been brought under the England and contained a faction that might at any time try a rebellion and Eastward from the Suez Canal there are immense fanatical hordes that have never bent under any yoke and might be eager to go on a murdering and marauding expedition. Could all these be persuaded to join in a great holy war? Germany reckoned on easily becoming the master of the world. That she herself might have been swallowed up by the flood she wanted to let loose, that she had allied herself with barbarism against civilisation, were items she never considered. Her objective was to rouse the coloured races to arms against the West and whoever lost in that awful turmoil she was bound to gain.

As usual, the German was not as clever and well informed as he thought himself to be, otherwise he might have known that the Mohammedan world did not hang together, that whatever the spiritual power of the Sultan might be actual ability to control his spiritual subjects was even less in political affairs than that of the Pope of Rome and than many of the Mohammedans knew on which side their bread was buttered and preferred the just British rule to the tyranny of ignorant Moslems.

Meanwhile Great Britain had to guard against the peril that had been created by the intrusion of the Turk and the danger was greatest in Egypt, whose geographical position constituted her a vital spot in the Empire. An immense British army was massed around the pyramids and the Suez Canal, ostensibly to complete their training, really to stamp out instantly any smouldering fires of rebellion that might break out. There were over 100,000 British troops in Egypt when the Turkish rule came to an end and the land of the Pharaohs became a British Protectorate.

Under the shadow of the Pyramids that stand like sentinels betwixt the mysterious Nile and the trackless Libyan desert did the Australians and new Zealanders pitch their camp. The newly made soldiers of the youngest nation pitching their tents by the battered graves of the oldest historical race. How strangely the two seem to mingle, just as curiously as the description Jack gives:-

"The other day when we marched past Sir George Reid, the High Commissioner for Australia, we received special mention of the G.O.C. (General Officer Commanding). The whole of the Australian forces at Mena Camp were marched past during the afternoon and our battalion was the only one I think that came in from work and did the ceremonial parade in dirty dusty conditions. All the others had a spell and got themselves up for the occasion. Of course Georgie made a patriotic speech and lauded us to the skies and in his peroration especially asking us to be a credit to Australia in the forthcoming struggle as well as in Egypt. Anyway Bill (Mr W. Turner), inspiring it was to see between 20,000 and 30,000 Australians saluting the High Commissioner for Australia and also the High Commissioner for New Zealand with Major General Maxwell the G.O.C. of the Army of occupation, of the New Zealand and Australian troops and all the respective Brigade Generals and Staff Officers under the shadow of the Pyramids. It was absolutely unique in the annals of Egypt, was it not?"

Nothing grows in that desert that borders the land of the Nile! It is pure, unadulterated loose sand, and in that loose sand our troops received their final training. How the boys must have longed for the granite of Black-boy Hill.

"We are at present engaged on brigade training, which means that the four battalions work together in all kinds of attack practices, night marches, and night attacks on imaginary trenches, etc. The latter is most cordially detested by all, I think. It means that generally about 7 p.m. we move from camp to a rendezvous where we meet the other battalions. From there we move on together with one platoon company on either flank in echelon formation to protect the flanks. We move with broken step, and of course, no light, no talking, and no smoking. So we stumble on in the darkness over undulating sandy desert until we reach the point where the charge is to be made. Nothing is forgotten. We even halt before we reach the trenches, and some creep ahead and cut the wire entanglements. When all is ready and without any sign that the listener could detect we form into line. Ten paces between each, and charge up some strong and steep hill in silence. After that we usually dig ourselves in and wait for dawn. Can you wonder that this phase of the training is not very popular? It is amusing to watch the malingerers parading before the doctor on the morning before a night attack or outpost duty. You see them don their overcoats and comforter caps, and without shaving or even washing they go down with some purely imaginary yarn. A well simulated husky voice, a pathetic woebegone look, and they are allotted light duties for the day which absolves them of parades till the following morning. On coming out their friends make sympathetic enquiries such as "Did you strike a prize , mate?" and then the patient nods if he has been lucky, and with a merry smile scatters the physic to the winds and races for a good breakfast."

The sick parade was mostly crowded when heavy work was on the notice board, but on holidays there was scarce any patients. No wonder, for it was only on leave days that the boys could see the wonderful sight of Cairo and its suburb, Heliopolis, and do their shopping. The descriptions Jack Turner gives, wet one's appetite to go and see. Right from the start the Australians were popular among the natives, but Jack thinks they had more money to spend than other soldiers.

"The shopkeepers are very obliging and obsequious; they will show you all they have in the shop, but will persistently ignore your request to get you the thing you want. No use being in a hurry." "To give you some idea of the shop which one sees so often here, I will try to describe one where all sorts of scented cigarettes and scents are sold. The floor of the shop is raised about three feet (1m) from the street level, and the front of the cabin of a shop is open to the street. The proprietor sits cross legged on the floor, and can practically reach all his goods without rising. Here he sits all day long and smokes cigarettes or pulls at his long Turkish pipe patiently waiting for customers. My friend and I halted here and sat down on the chairs in the narrow street, which were provided for our comfort. We were told that here was the home of the famous 'Ambai' cigarettes and 'Ambai' scents. The fame of the goods was world-wide, we were given to understand. All the elite of Egyptian society and hundreds of the fashionable ladies and gentlemen of the whole world patronised those cigarettes and scents, and he was surrounded by hundreds of testimonials to that effect, whilst in this book - here he produces a huge book-where hundreds of illustrious names, for each of his customers was asked to sign his or her name in that book. (What a chance to hob-nob with the great! I fancy I can see the grin on those two soldiers and hear their irreverent remarks, - Ed) Would your Excellency try a cigarette and please to write in this book. That of course meant we were asked to purchase as only customers wrote in this huge ledger. I accepted a cigarette, but as I did not like it I did not write in the book. I also read the testimonials, which were original and true enough, and showed that a number of English ladies showed a partiality for 'Ambai' cigarettes. I suppose it was a taste they acquired while touring in Egypt. Here this fat Egyptian sits like a Pasha on his throne."

Jack made the most of his time on the days when he had leave, visiting gardens, pyramids, mosques and shops. and pages could be filled with descriptions as interesting as the foregoing, and yet every letter contains the strident wish to be sent to the front to do the work for which they had enlisted. That Egypt itself was a danger zone, and that the army was there to overawe the malcontents, and might have at any time some real fighting to do, did not occur to most of our lads, and yet they got information now and then of serious brushes not far away. There is an allusion to one in one of the earliest entries in his diary:-

"25/2/15. Route march to the Zoo. Saw two galvanised iron pontoons captured from the Turks at the canal. Stayed about two hours, and went back. The 3rd Section, 3rd Company Field Engineers returned from the canal during the evening. Saw Fred Fancote; he is well, and had a very interesting time at the canal. Turks gained the canal at one point, but were stopped by patrol boat with machine guns. The old pilot who piloted the Medic through the canal lost one eye piloting a war boat into action in the lakes of Ismailia. The Girka's fought well and were placed in position on both flanks of the British forces. The presence of barbed wire entanglements stopped the Turks at Kantara and Ismailia, otherwise they would have crawled right up to the trenches. There was only a small force on the Egyptian side of the canal, and only dummy trenches on the Asian side. There the Turkish attack was strongest".

Evidently Jack gathered his information from Fred Fancote, who was in the Engineers, and with whom he went to the pictures the following evening. These two were close companions in Australia, enlisted at the same time, but came to be placed in different corps. This is the first recorded meeting, but they met very often afterwards.

LEMNOS This island in the northern portion of the Aegean Sea is classic ground. It lies half way between the coast of Asia Minor, where ancient Troy is situated, and Mount Athos, on the European mainland. Paul passed it when the Man from Macedonia beckoned to "Come over and help us," and of late years Macedonia has cried and cried again to be delivered from the tyranny of the Turk. This time it seemed as if the day of deliverance was near to come. Lemnos became the gathering place of the Allied Fleet and forces before entering the Gallipoli campaign.

On the last day of February, 1915, the 11th Battalion struck their tents, marched from camp at 6.45, reaching Cairo at 10.15, and went straight on to the train which bore them to Alexandria, where they shipped on the liner Suffolk.

"Taking on board enough stuff to equip an army corps; ropes, barbed wire, timber, picks, shovels, ammunition, etc. Country between Alexandria and Cairo very grand indeed. All beautiful agricultural country with irrigation everywhere. Canals, twenty feet wide, on either side all along the railway line."

The lads had not much chance to go sightseeing, for HMT Suffolk together with other troopships, left on the 2nd March, and steamed northward into the Greek Archipelago. The Suffolk reached Lemnos on the evening of the 4th March, and came to an anchor in the landlocked harbour of the island. Six French and British warships were there at the time.

The attempt to force the passage of the Dardanelles was being made. Warships with specially constructed guns were bombarding the Turkish forts, destroyers were hunting down enemy submarines, and minesweepers were clearing the waters of dangerous obstacles. Lemnos was being used as a base of operations, and the various craft thus employed made their appearance periodically in the harbour together with the prizes they captured, and troopships, cargo tramps, oil and coal steamers coming there in ever greater numbers, with the soldiers and the sailors from many nations, must have produced a very animating picture.

The (Boys) were kept at work training in dead earnest. There were trial embarkations, instruction in discipline in the field, physical and visual training, route marches and bathing parades, with an occasional day of guard on shore in company with Senegalese and Algerian troops and blue jackets, varied with loading and unloading materials for the campaign for which the armies were gathering.

They knew but the barest outlines of what took place within a few miles of them, though they had ocular demonstration of the ravages of war in the spectacle of battered ships coming into port.

Can see snow capped mountains [Mount Athos probably], which are only seven miles from the Dardanelles.

Two German cruisers are cornered in the Adriatic and will have to surrender.

Received news of German submarines having been sunk in the channel.

Rumour going to land 100,000 troops in Turkey.

Believe we are waiting for 20,000 French and all the Australian and New Zealand troops.

Seen forts demolished up to the time the marines left and minesweepers going on.

Such were the scraps of information that drifted in among the men of the 11th Battalion. They were uncertain about their future for even as late as 4th of April he mentions in his diary:

"Received news that we are leaving shortly, destination unknown. Some say Malta, others Dardanelles".

In the course of time some of the sick that had been left behind in Egypt, joined them on their recovery and brought news of another kind:

"Some of the boys went mad and burnt down several brothels in Cairo."

Better if the boys had never gone near them. The Australian hospital ship also made its appearance in the harbour. There appears to have been hospital accommodation ashore also, for on two successive days he makes the following entries:

"30/3/15, A man named Rose from Capel, W.A. died from pneumonia in the hospital on shore. 31/3/15 Morning rifle drill and physical training. Afternoon about 20 men and Lt. Macfarlane went ashore on guard. Also some from D Company. Guards posted on two roads running from Mudros town to guard against spies. Also on the small wharf. We were on the wharf which was very busy, English, French and Russian naval officers passing to and from all day. English officers were smart and very jolly looking. They affect the monocle very much. Many French officers wear the Legion of Honour. The Inflexible which was battered up a bit last week is in harbour. She has still a bit of a list. French, Senegalese and Algerian soldiers on guard near us. Their rifle and bayonet together a foot longer than ours. They fought at Mons. Our mail arrived at last. Mudros quite a busy scene with so many soldiers and sailors. Very pretty church here. Saw the military funeral of the late Private Rose of D Coy., 11th Battalion."

On Friday, 23rd April, 1915, three days rations and 200 rounds of ammunition were issued to each man and on the following day they embarked on the (HMS)London at midday, left Lemnos at 1.30 p.m. and landed on the Gallipoli Peninsula at 4 a.m. on the Sunday morning, 25th April, at a spot which has since became famous as Anzac Bay. The name sounds Turkish, but it is not. It is the compound of the initial letters of the Australian troops - the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps.

THE LANDING Another generation will probably have to pass away before an adequate judgement can be formed of the wisdom of the leaders in attempting to force the passage of the Dardanelles. At the outset it looked impossible, but then it has always been a characteristic of our race to try the impossible. We shake hands with ourselves if we succeed and say in an off-hand manner that we knew we could do it, and if we fail we call ourselves fools, which is another of our characteristics.

To our Australians, fresh from the pastures, wheat fields, mines and workshops, fell one of the hardest tasks that could be given to any kind of troops. They proved to be of the old bulldog breed. "theirs not to reason why."

They were told to go and they went; those who fell, fell with their faces to the foe, and the remainder did not turn back until they were told to go back. Anzac is henceforth an historic name; it is the appellation of men who were not bred for war, did not want war, will go back to the old job when it is over, but who fought as hard, and with as much courage and skill as the best veteran soldiers who ever fought on any field. Hats off to the Anzacs, and let no Australian ever fall short of their standard.

Here are two letters which deal with the landing and the very earliest stages of the Gallipoli campaign. We attach much value to these letters; they were written on the spot when the events were fresh in the mind and they also bear the counter-signature of "Macfarlane", the Lieutenant, now Major, whom Jack frequently mentions in his diary.

14th May 1915Dear Dad, Am very pleased indeed to be able to say I am well this afternoon, and you believe me, Dad, to be able to say that at this stage of the game is something. You know, Dad, the A and C Companies of our Battalion (the 11th) came around here on a warship (H.M.S. London) and landed under heavy machine-gun and rifle fire on Sunday 25th of April. So that we had our baptism of fire before we landed at all. As soon as we touched land we got rid of our packs, fixed bayonets and straight up the hill after the Turks. But for the most part they did not wait for us near the shore and we got about a mile inland without many casualties. It was a terrible climb, as the hills were so precipitous, but Sunday night found us lying on the table land in one long, thin line which neither shrapnel of machine gun or rifle fire could shift. But the casualties of our Brigade were awful, Dad, for the first few days, for we could only dig in during night times and when the enemy was not pushing us too hard, while they were entrenched in stronger positions and in such great numbers where they have been waiting for us for weeks.

The Monday and Tuesday were even worse than the Sunday I think, as the Turks had our range to a nicety with their shrapnel and machine guns and you bet every spare firing line to carry ammunition for the rest of us. But, personally, I did not eat much for the first few days. Didn't seem to have much time for meals. I think that every one acted real well and specially our machine gun stations. Their fire was very...................minute we were burrowing like rabbits. But on Monday night and Tuesday night the Navy made the trenches of the enemy a picture, I can assure you, and relieved us to a great extent. We started with three days rations and our water bottles full, and of course until Tuesday night could get no more, as every available man was required when not in the......... deadly indeed. And no praise is too great for the ambulance men, stretcher bearers, and doctors. Their work was grand indeed and always has been. It is so full of danger for they have to come right into the firing line to take the wounded away. On Wednesday night we were relieved and went down to the beach for a few hours. And on Thursday morning it was sickening to see how many of our fellows had been hit. So many of one's palls were missing when the roll was called. Dad, and I think it was not till then I realised how awful war is. Anyhow, since then we have heard of lots of them who are eager for their wounds to heal so that they can rejoin us. Old South African soldiers tell me that they never saw such a terrible time in the Boer War. Such an awful lot of ammunition was used by the Turks as we advanced that it was a marvel that we were not annihilated. Their fire was continuous for the first few days. Sometimes it seemed to literally rain lead, but their shooting, generally speaking, was bad. During the night they would advance in large numbers as if to charge us with the bayonet, but they always thought better of it before coming too close and retired without trying the cold steel. Now, Dad, I am limited to one page so I must close for the present. Haven't seen Fred Fancote since we landed, but believe he is alright.

With love to all, I remain your loving son, Jack Turner

Gallipoli June 15, 1915. Dear Mother, Our mail has arrived much more regularly. I got letters from you, aunty, Dad, and Daisy. Also papers, magazines and parcels. Thanks so much for the pipe and socks Mother. I am quite well off in regard to the latter now. Your letters, you know, are the most appreciated things I get out here. Mail day is always the most important day of the week by far. It is good to hear news from home and your letters are read and re-read again and again.

Yes, you must have spent some anxious time after hearing that we had received our baptism of fire until the belated casualty list came through. I cabled to you that I was well on about May the 3rd. Did you get that cable?

Yes the landing was a great trial to a lot of untried soldiers, especially as we drew in shore. The bullets were so thick and in the half light of the dawn the shore seemed terribly precipitous and the scrub so dense that one imagined all sorts of dread possibilities in regard to ambush, etc.

Personally, I did not think that we, being the first to land, would last long on the beach if the Turks has any go or fight in them at all. But they did not wait for us to close with them when we landed and we lay for a few minutes or so on the beach to rid ourselves of our pack and then, without forming up or waiting for the other boats, we tackled the hills through the dense undergrowth in a straggling line, every one doing their best to catch the elusive Turk. But that climb was awful, Mother. We had 200 rounds of ammunition, which together with three days rations, water bottle, rifle, and equipment made a heavy load. But the sailors on London had looked after us so well and fed us so often during the few hours we had been with them coming from Lemnos that we managed to scale those hills alright, and eventually established ourselves on the third ridge. We then dropped down and just held on, keeping the enemy back and in our spare time digging ourselves in.

During the first few nights the Turks would come up in large numbers quite close to our small entrenchments and with much blare of bugles and shouting "Allah" would make believe that they were going to charge. This they rarely did anywhere, but the noise was awful.

You see they brought up machine guns and placed them in good positions and tried to entice us to charge them. Had we done so they would undoubtedly have mowed us down with those machine guns. They tried all sorts of dodges to outwit us, even to coming into our lines in disguise and passing down false orders, but those ruses failed. During the day time the firing was incessant and the shrapnel was awful and reinforcements were coming up fast for the Turks, but we were also extending our line, until it reached right across the point from shore to shore. This relieved us from the enfilading fire which at first came from both flanks.

It is impossible to tell you in a short time all that happened right up to Wednesday when our Brigade was relieved for a few hours and we went down to the beach for a rest.

I did not eat much and slept less during those four days and had to go sparingly with my water for the supply could not be replenished. My hat was shot off while observing one night and my trench was filled with shrapnel bullets and dirt once while I was out in front on battle outpost, but apart from a slight graze on the top of the head, I was unhurt. So that I was very lucky. The string of wounded was going down to the beach night and day during that time and the work of the stretcher-bearers was worthy of every praise, and several times I saw fellows helping a comrade down the valley to the dressing station under heavy fire. I also saw fellows jump out of the trench and gallop across the level ground behind us with a couple of water bottles and later on they would come back with a renewed supply or perhaps they wouldn't come back at all, having been shot by a sniper or a spent bullet in what we now call Shrapnel Gulley. I don't think we realised the full amount of danger. I know that after the first few minutes in the boat that personally I thought the bullet was not moulded that would kill or wound me. You know one seldom thinks of the risk as there is so much to see and do all around and you are so intent on shooting the other fellow that it seldom occurs in the heat of the engagement that he is shooting at you.

It is not bravery at all, It's just a feeling of superiority we seem to have inbred in us over the other fellow. The Turks have been a fighting nation for generations and are led by the greatest Military nation in the world and yet I don't believe you would find one amongst us who did not believe that our army which is not a year old yet, is not vastly superior to the Turkish army. This confidence is a great help if not carried to the extreme.

Tell aunty that the paper and envelopes which she sent have saved the situation. One can buy nothing here. Just at present I am in that particular predicament of having money in my pocket and being unable to spend it. I landed with fifteen shillings in my pocket and I still have them all. Gallipoli is a great place to save money in. I never felt better in my life.

GALLIPOLI The soldier on the spot knows less of the progress of the war than the newspaper reader many miles away; he is often ignorant of the purpose of the campaign and sees little beyond the field in front of him, but it is just because he is on the spot and the details around him are branded on his memory that his records, if he has the skill to make them, are so valuable and become ultimately the materials from which the future historian must build up his tale. We therefore select portions of Jack's Diary. They describe tensely and graphically the common round and dangers of our men.

Tuesday, 4th May, 1915Came out of the trench on Monday night when 100 volunteers of A Company of the 11th left for the beach to wait for the early morning to storm the BB fort and observation post about two miles south of our right wing. We went by torpedo boat at 4 o'clock this morning and proceeded to a place opposite the fort. From here we were rowed ashore by the blue jackets.

When we got within range three machine guns and one pom-pom opened fire. Also a withering rifle fire. Some were hit in the boats and many killed rushing across the beach. We had not a fighting chance as the ground was as clean as a lawn and swept by their fire. Should never have returned if it had not been for the navy lads. They sent a boat for our wounded and afterwards shelled beans out of the fort, while they sent boats for what was left of us. The work of the navy was wonderful. One torpedo boat fired two hundred rounds at the fort while we were getting off. The Fort looked a picture while it was going on, for the Turks kept well under cover.

Saturday, 22nd May, 1915 In the firing line all day. Yesterday the German General in command of Turkish troops came in under the white flag to consult. Turks say they lost 3,000 killed and 5,000 wounded by that night attack on the 19th inst. last and since. They came right up to the trenches six deep in places. Turkish dead cover eight acres in front of our trenches. The stench is awful.

Saturday night. Formed one of reconnoitring party to discover Turkish strength in front of our section about 200 yards in front. Turks opened fire on us with five machine guns and rifles. Lost one man called Smith from D Coy. The rest got back alright.

Sunday, 23rd May, 1915 The battleships were shelling the whole plateau on our right this morning. Think that they were giving Turkish reinforcements a dose of shrapnel. German aeroplane just sailed overhead and dropped a bomb in front of the trenches in Hell's Gully. Killed one fellow from the 10th.

Two days ago the 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, and 9th Light Horse landed, also many reinforcements. Strange to say the enemy did not give them their initiation of shrapnel. Could hear them cheering as they landed. Yesterday all the warships and the torpedo craft were steaming about looking for enemy submarine, reported to be in the harbour. Things were very busy. All the transports cleared out for awhile.

Reported that dysentery is rife in the Turkish camp. Also that they are short of arms. Am going out with a party collecting arms from dead Turks in front of the trenches tonight.

Battleship Albion and others shelled Turkish reinforcements for an hour and twenty minutes continuously over a front of four miles. Armistice tomorrow from 7.30 a.m. till 4 p.m. to allow Turks to bury their dead. Emery saw Allan Cook on the beach yesterday. He is well.

Monday 24th May, 1915 Lots of Turks came out half way to our trenches where our burying parties met them. They are now going along each on their own side picking up the wounded, burying the dead and sticking the bayonet in the grounds to indicate where the soldiers fell. The Turks have also lots of dead behind their own trenches in the scrub where our artillery shrapnelled them as they moved up to their new position. Turks wear a light uniform and some wear blue trousers. We killed more than I thought the morning of their attack. Can only see a little of what is going on. The order is to keep out of sight.

Tuesday 25th May, 1915 Yesterday afternoon Fred Fancote came up to see me before he went into the firing line. He is looking very well indeed. Has been busy with engineering work all along the line. Had a long yarn with him. Last night things were fairly quiet, although hostilities were resumed at 4.23 p.m.

Today at 12:30 H.M.S. Triumph was torpedoed close in shore by a foreign submarine. She was hit amidships and soon settled over on her port side. Many torpedo boats and trawlers, also pinnaces made from all quarters to her rescue. One torpedo boat and two trawlers were close to her as she gradually turned turtle and sank. For some minutes she remained keel uppermost, but eventually she went down in a maelstrom of foam and steam. Dozens of torpedo boats went in all directions, also warships, searching for the submarine. reported that the crew of the Triumph are lined on the beach, that only 28 were lost and that the submarine has been sunk. The most regrettable part of the affair was that the Turkish batteries shrapnelled the trawlers and pinnaces which formed the rescue party. We could see everything and saw the shrapnel burst over the boats and hit the water where the sailors were swimming. She sank in about a quarter of an hour after the torpedo struck her.

Wednesday, 26th May, 1915. In reserve last night. Also today. Jim Smith shot through the head at 2 o'clock this morning. He was putting sandbags on the parapet when sniped.

Went over and saw Fred Fancote this afternoon. he showed me the place where the Turkish trenches overlook the valley and the point from which they snipe so many of our fellows.

Twenty were sniped today. Two were hit early this morning while sleeping. The 16th lost a lot there. Also the Marines. Got back at 5 p.m. and went straight to the firing line. Bi-plane dropped two bombs on Turkish trenches just in front of us.

Tuesday, 8th June, 1915. In supports during the morning, but told off for tunnelling operations in connection with a new firing line in front of A Company. Went on shift at 12 mid-day.

No 3 Platoon of A Company [Jack Turner was a member of this platoon], with a platoon of each company in our Battalion were sent to capture a trench 250 yards to our front under Major X. X was drunk. R never left the saps and M lost his way and his nerve, consequently the result was a fiasco. Which was a disgrace to the Battalion. They came back at about 3 a.m. after having got bushed and scared and having made no attack at all.

Thursday, 10th June, 1915 Went on shift at 12 p.m. D Company went out to capture the trench last night, but the Turks were strongly reinforced and the attack failed. Went round to Shrapnel Gully this morning. Snipers still bad. Fred Fancote is around here spelling with his company. Turks are very short of ammunition, specially shells. Hardly shelling at all. They evidently understand the art of trench digging. Each trench, if captured, can be enfiladed from each flank. Those we took had to be left again at daybreak. They were also good at creeping up individually and sniping close to our trenches. Early in the game single snipers were caught inside of our line, right in our midst. One had 19 discs in his possession. They also hide their machine guns well.

We are handicapped for want of scope for our artillery for we cannot manoeuvre them at all. These field guns are run out and a few shots fired as quickly as possible and then run back into the pit before the enemy can reply or they would be blown to pieces. The 8th Field Artillery have been especially complimented by the Brigadier-General. They are from W.A.

Saturday, 12th June, 1915 One of our fellows killed last night while observing in firing line. He was one of the 4th reinforcements, a fellow named Grant. Sharp artillery duel has been proceeding since daybreak. Our howitzers and field guns are going some. The enemy is replying with both shrapnel and percussion shell, but doing little or no damage. Their shooting lately has been very poor. Some time since they fired 360 shells into our supply depot with the result that they mortally wounded two biscuit boxes.

Of course we are subsisting on a ration of biscuit, a piece of bacon, also cheese and three ounces of jam. Also a few onions and a tin of dog per day. The food is plenteous enough, but one longs for bread, especially those with false teeth, for the biscuits are hard whether flour or oatmeal. Our cook usually makes a stew of our onions and meat. Once every few days we have some steak, which is very much appreciated. Water also is none too plentiful here. All our water has to be carried from headquarters or from Shrapnel Gully. Hardly any sickness in our lines.

Wednesday 16th June, 1915.

Moved into supports at 9 a.m. just behind the firing line. Double issue of rum and issue of tobacco. Much bomb throwing last night. Bomb burst in Pat Foley's hand before he could throw it; blew his hand off and otherwise badly wounded him. Also wounded Corporal Robinson, Corporal Clifton, Tim Shay and a stretcher-bearer. Very sad affair.

Mail days were the red letter days in the trenches, eagerly anticipated and diligently prepared for, but in the fighting days the correspondence was restricted to very small epistles. We make some extracts of the last two letters written by Jack.

Gallipoli 23rd July, 1915.Dear Mother Thanks very much for the letters and the papers which I received this week. Yes I get your letters very regularly now, also papers and chocolates. Trust that you receive my letters and field service postcards, one of which I send every week. Things here are much the same as when I wrote last week, except of course that someone or another is always getting hit and so one misses a familiar face for awhile, perhaps forever. You know the few of the old platoon that are left are like brothers, and it hurts when one of the old hands gets hit more than the new ones. Perhaps it should not be so, but it does. The weather here is grand. Bright sunny days and long evenings. Do you remember the 'Plough' or was it 'St George's Wagon', which we could see in the western sky in England? I see it every night here from my dug-out. But often I would prefer to see the 'Southern Cross'. Those dug-outs are just holes cut in the hillside where we rest when not in the trenches. You wished to know something of the rations and kindred things. Well, we get bread every alternate day and at other times biscuit. We are also issued fresh meat fairly often and potatoes and onions, which our platoon cooks nearly every day. Furthermore we get a piece of bacon, cheese and a ration of jam every morning. So you see between the assortment we get plenty to eat. As I told you, water is scarce, but we get enough to drink and one gets a swim occasionally during the evenings.

We get a few cigarettes and a little tobacco issued once a week. This issue is a bit light for a hardened smoker like myself. Now, Mother, I must close. Letters are supposed to be short ones, but this will suffice to let you know that I am well so far. Trust that all at home are well.

With love to you all, I will say again "au revoir." From your loving son, Jack.

Gallipoli, 30th July, 1915. Dear Mother, Our mail has not arrived this week, so that I shall not be able to answer your letter when our belated mail arrives. Will write you longer next week. We are in reserves: that is to say we are having a spell, which is much appreciated by all. The weather still continues dry and splendid. The sky unflecked by a single cloud and the sea as calm as the proverbial mill pond. Trust the season continues propitious and that W.A. has an abundant harvest this year. Thanks very much for the papers which I received last mail. Up to date I am alright. Next week I will write a longer and more interesting noter. So for the present I will say "Au revoir", with much love from your loving son Jack.

"Our reinforcements are here. There are 90 for A Company."

This was the last letter written by Jack, and his last diary entry is dated 4th August, 1915

Notes

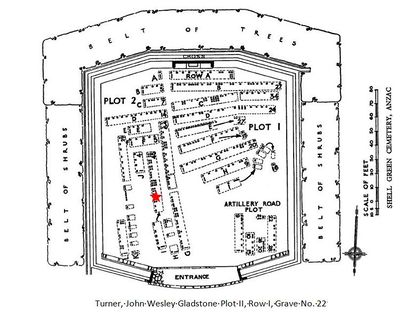

Buried in Plot II, Row I, Grave 22 SHELL GREEN CEMETERY GALLIPOLI About 1150 yards (1000 metres) south of Anzac Cove. Buried by Chaplain TG Robertson

- ↑ 1915 Sept edition:

External Links

- WAMDL - Western Australian Military Digital Library has digitised some of John Turner's military records.

- AIF Project

- RSL Virtual War Memorial